Against the backdrop of Australia's arid and red clay, the Mount Holland (Mount Holland) lithium mine is presented in front of approaching visitors in front of a huge grey crater. Trucks the size of a house are parked on a steep hillside.

The $2.6 billion ($1.7 billion) project is located at the center of the world's largest lithium production area and is an expanding base. It symbolizes the huge supply of lithium battery materials that are pressuring current global prices, most of which come from this region. Despite bullish long-term forecasts, the metal's price has been hovering around a two-year low due to a mismatch in downstream demand.

But this huge mining area also gave us a glimpse into the future of Western Australia, or rather, this vast region that has been defined by the needs of the Chinese steel industry for decades, hoping to enter a new, more environmentally friendly stage of development. This battery raw material still accounts for only a small portion of exports, but its prospects have attracted the attention of some of the region's biggest and boldest mining companies, and attracted multi-billion dollar investments, from Gina Rinehart (Gina Rinehart) to Chris Ellison (Chris Ellison) Mineral Resources Ltd. (Mineral Resources Ltd.).

Mount Holland, which is jointly owned by Chilean mining giant Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile and Australian conglomerate Wesfarmers Ltd., is one of the largest businesses established in Western Australia in recent years. A processing plant opened last month, and a refinery will open next year. The final production of lithium hydroxide is enough to power nearly 1 million new electric vehicles every year for half a century.

The problem is that the industry has been expanding, and overcapacity has forced some companies to press the pause button and may prolong the downturn that has hit the industry hard.

The International Energy Agency predicts that lithium demand will increase 40 times over the next 15 years from 2020-2021 due to demand for batteries and electric vehicles, which will require dozens of additional Dutch mountains.

Ricardo Ramos (Ricardo Ramos), CEO of SQM, the world's second-largest lithium producer, said: “At the beginning, it was an adventure for us, but now it's the future.” Most of SQM's products come from Chile, but its mining contract in Chile expires in 2030, and future prospects are uncertain.

Ramos said, “As we speak today, I want Australia to have ten more Dutch mountains; one won't be enough.”

Chile has the most extensive natural resources in the world so far, and has mineral-rich salt beaches. But apart from Latin America's “Lithium Triangle” (Lithium Triangle), which includes Argentina and Bolivia, Australia has the most abundant lithium reserves in the world. Lithium is an important component of rechargeable batteries and is at the heart of the electricity revolution.

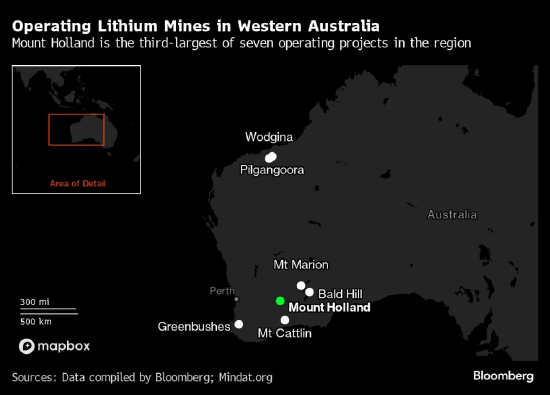

The ability to rapidly extract lithium from hard rock resources, combined with existing infrastructure, means that it has experienced a certain boom in development. In 2016, Western Australia had a lithium production mine. Today, there are seven. In 2000, the country's supply accounted for about one-sixth of the world's supply, and now it is extracting close to half of the world's production, almost double Chile's production — a figure that is quite impressive even though China still dominates refining capacity.

In a context where mining history dates back nearly two centuries, the passion for this ultra-light metal is relatively new. Until recently, Western Australia's largest investments were focused on higher-revenue projects, such as iron ore, which supports the world's largest miners. Lithium is being used to treat bipolar disorder and is even used to harden the glass of perfume bottles.

“It used to be difficult to do a business; we all had bells hanging up in our office. Dale Henderson, CEO of lithium producer Pilbara Minerals Ltd., said: “In the past, when we finalized a deal, we would ring the bell and the whole office would cheer.”

“We'll call the scene and say, 'Reopen the factory, we have a business'. That was just a few short years ago.”

Like everyone else here, Henderson saw hesitation from investors and some developers. However, he believes that the lithium market is relatively young, which means that the sharp drop in prices last year and the leveling off in demand for electric vehicles should be viewed as growing annoyances.

Of course, billionaires who have made a fortune in the iron ore industry and need to find new bets for the future also continue to pour into the metals industry brought about by the energy transition. The main known lithium investments of Reinhart and her company Hancock Prospecting (Hancock Prospecting) alone are worth close to $1 billion at current market prices — not including copper, rare earths, etc.

However, the question is whether veteran producers, tycoons, and even Western Australia can apply their previous experience in bulk materials to battery mining, processing, and downstream supply chain capabilities, making full use of free trade agreements with the US and other markets to provide another growth point for the Australian economy.

It also faced some major obstacles, including a higher carbon footprint than producers such as Chile. Considering the energy intensity of hard rock processing and the technical challenges surrounding lithium hydroxide production, these challenges even hampered the production of heavyweight Albemarle Corp., which was also hit by delays and increased costs after the pandemic. Australia's first lithium smelter in Kwinana was a joint venture between Tianqi Lithium and iGO Ltd., which began production in 2021. Since then, it has been difficult to achieve expected production volumes, and expansion plans have been put on hold.

Mining has been integrated into the structure of Western Australia since the earliest times. Western Australia is roughly the same size as Western Europe, and its population is only half that of the small country of Singapore. The industry can be traced back to the gold rush of the 19th century, but it was the awakening of the Chinese economy that created a boom in steel and iron ore. This boom was so great that it helped the Chinese economy avoid the global financial crisis and cushion the impact of the pandemic.

Currently, due to various factors, steel producers are under pressure to clean up this industry, which accounts for at least 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Australian iron ore earnings are expected to decline. According to government forecasts, Australian iron ore earnings will fall from 136 billion Australian dollars this fiscal year to only 83 billion Australian dollars by the 2028-29 fiscal year.

Lithium batteries will not be able to fill this gap in the short term. Even in 2028-29, exports are expected to be just over $9 billion.

To expand the impact of the lithium boom and bring benefits in terms of export revenue and job creation, Western Australia needs to expand its geographical advantage and double investment in other battery materials, including copper, all of which require some policy support. Following the development of a key mining strategy last year, the Australian Government said it is planning to take further steps to support downstream processing.

Citi (Citi) analyst Kate McCutcheon (Kate McCutcheon) believes that Australia has an advantage — rich hard rock lithium resources, suppliers that comply with the US Inflation Reduction Act (Inflation Reduction Act) may benefit from price premiums, and more domestic processing processes, which is a green benefit.

But challenges remain, including high costs and energy supply, not to mention managing the limited shelf life of lithium hydroxide — usually it starts to degrade after six months — and the lack of potential to expand further into battery production.

“You're competing with other countries that offer attractive tax holidays, lower labor, and energy in certain areas. To date, downstream projects outside of China have proven to be more difficult to operate and far more costly than anticipated.”

Back at Holland Hill, Western Australian Governor Roger Cook pointed out that the increase in lithium deposits in the mine last year brought more royalties than gold mines. This is where the state and Australia will drive the next steps.

“Let's not lose our vision,” he said amid the crackling of crushing ore. “Demand is still growing, and we're here to meet it.”